HOSSFELD WINS

WORLD TYPEWRITING TITLE

FOR TENTH TIME

Records were already being broken before the first competitive typist touched a keyboard in the 1937 World Typewriting Championships at the Coliseum in Toronto.

Staged as part of the Canadian National Exhibition of 1937, the typewriting championships drew a record number of 106 entrants from across North America and Japan.

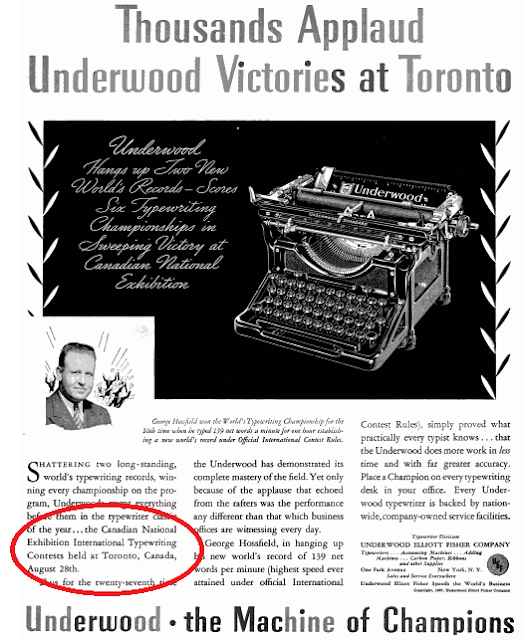

The Underwood team of both professionals and amateurs, led by the remarkable George Leonard Hossfeld, massacred existing speed typing records under revised competition rules.

Hossfeld, then living in West Englewood, New Jersey, won the $500 first prize and retained his world professional title by scoring a rate of 139 words a minute over one hour. He made 43,282 keystrokes in writing 8656 words. That's 721.4 keystrokes a minute for 144.3 words a minute (five-letter words on average), but he was deducted points for his 31 errors.

Hossfeld had previously won the world professional title in 1918 (aged 19), 1920, 1921, 1922, 1926, 1927, 1929, 1930 and in Chicago in 1936. He also won the amateur title in 1917, for 11 world titles all up.

In Toronto in 1937, Hossfeld again beat Cortez Wilson Peters (born Maryland, December 23, 1906; died Washington, December 1, 1964), as he had done in Chicago the previous year, and Barney Stapert, of Hawthorne, New Jersey, to hold on to his crown.

Cortez Wilson Peters

Twenty-two-year-old Grace Phelan, of Etna, Pennsylvania, won the world amateur championship with 129 words a minute over 30 minutes, with only nine errors. She made 19,783 keystrokes for 3957 words (659.4 keystrokes and 131.9 words a minute on average, before a deduction for errors).Phelan beat hometown girl Gladys Mandley and Irene Martine of Oklahoma City.

And didn’t Underwood go to town on these achievements? See the series of attached advertisements.

The big venue, opened as the Civic Arena in 1921, the largest structure of its kind in North America at that time, is nowadays known as the Ricoh Coliseum.

Reports at the time stated there were also “six major touch-system championships” held in conjunction with the speed typewriting titles.

The championships had returned 49 years later to the host city of the first world speed typewriting championship, held in Toronto on August 13, 1888 (and won by Mae E. Orr, a two-fingered typist using a Remington, or Thomas W.Osborne using a Caligraph, depending on whether one accepted the Remington argument about the outcome or the Caligraph argument.)

According to Pitman’s Dictionary of Typewriting (1932), George Hossfeld (Pitman’s spelt his name “Hossfield”), “gained his knowledge of touch typewriting from A Practical Course in Touch Typing written by Charles Edward Smith”.

Smith, apparently, had been a world champion speed typist who broke the early stranglehold on these events held by Remington and Caligraph, using an Underwood. He published several books on touch typing and was closely associated with Pitman’s.

Smith became coach of the famous “Underwood Speed Training Group” and developed the "right-hand carriage draw", a method of exchanging paper that saved as much as a full second. “This method required the typist to grab the roller knob and the filled sheet with one hand while grabbing a fresh sheet from a prepared stack of papers and inserting it without ever looking away from the copy.

"All of this in one-third of a second! Techniques introduced in the racing circuit gradually infiltrated the business world, producing typists with elegant and precise routines to synchronise their movements with the machine. Rhythm was key: ‘Above all, the mark of good typing is a continuous, even rhythm. An expert keeps going’.

INCONSEQUENTIAL NOTE: When Ernest Hemingway was working

as a reporter on the Toronto Star in the early 1920s,

he wrote to his father describing how, under his very nose,

sheets of copypaper were ripped from his typewriter

by copyboys as soon as he'd written one or two paragraphs

on them (the sheets, that is). That was speed reporting ...

Smith has been described as a “talent scout in secretary schools, coach, ergonomist and ruthless trainer of 'his' typists in the Underwood training hall at Vesey Street, New York”.Since Hossfeld had become employed by Underwood as a typing demonstrator and professional speed typist, he probably had no choice but to vouch for Smith’s methods. However, it seems that before joining the Underwood team, Hossfeld had acknowledged earlier influences on his typing techniques.

When Hossfeld won his first world title, in the amateur division in New York in 1917, aged just 18, it was claimed that his speed typing prowess came from his training under the “Barnes method”.

In the 1917 titles, Hossfeld was reported to have typed at a rate of 145 words a minute net (under the original scoring system) in the amateur class, two words more than Margaret B. Owen had achieved in winning the professional division “and eight words faster than the highest previous world's record”.

Further, it was reported that Albert Tangora, who was later to become Hossfeld’s great professional rival, had in 1917 won the novice-school division “after less than 13 months' practice” by writing 110 words a minute net.

“Both of these young men learned typewriting in Spencer's School, Paterson, New Jersey, from the Barnes Typewriting Instructor … It was after the adoption of that text (Barnes) that our pupils began winning the Eastern, American and national contests.”

Like Charles Edward Smith in the same period, Louisa Ellen Bullard Barnes (born 1850, Shrewsbury, Rutland, Vermont) wrote many books on typewriting instruction. In Barnes’s case, however, her first attachment had been to the Caligraph, before switching to Underwood’s abiding rival, Remington.

Her Barnes Typewriting Instructor was published in 1909 by her husband, Arthur J Barnes. In How to Become Expert in Typewriting, published in St Louis in 1890, Mrs Barnes had defined “write by touch” as “To learn to write by touch, that is, with only an occasional glance at the keyboard, sit directly in front of the machine. Keep the hands as nearly as possible in one position over the keyboard.”

George Leonard Hossfeld was born in Paterson, New Jersey, on December 5, 1898, the son of Johann Caspar Hossfeld (born June 22, 1863, Meiningen, Leipzig, Germany) and his Anna Hoerber Hossfeld (born of German parents in Paterson, August 7, 1860).

But for one of those simple twists of fate, George Hossfeld might never have been among us to win world typewriting titles. His mother lost her first-born child and was told she would not be able to have more children. Shortly afterwards, the Hossfelds’ neighbour died when her seventh son, William, was nine-days-old. Because the families were close friends, Caspar and Anna offered to care for Willie in place of the child they had lost. On June 6, 1891, the Hossfelds adopted the baby, giving him the name William Carl Hossfeld. On October 26 the following year, the Hossfelds welcomed son Elmer into the world. And more than six years later, George was born.

At age 19, George married Frieda Emma Marti in Paterson on August 29, 1918. They had two children, George and Bernice.

In 2002, a relative, Casper H. Hossfeld, wrote of his father and uncles, “All three attended St Paul’s Lutheran School and all learned to read write and speak German as an important part of their education. All three boys were given music lessons. Elmer and George took piano lessons and [Will] violin.

“All three graduated from St Paul’s but George went on to a school [Spencer’s?] where he learned typing. He was an excellent typist and entered speed typing contests where he was often a winner. As time went on he eventually won the international speed championship and held it off and on for many years.

“This got him a very good job with the Underwood company where he travelled around the country giving exhibitions at schools where the goal was to sell the school Underwoods.”

George Leonard Hossfeld died on January 10, 1972.

As a postscript on Peters, who I mentioned in a detailed post on world typewriting championships at http://oztypewriter.blogspot.com/2011/06/world-champion-typists-and-typewriting.html

along with Hossfeld and Tangora, this letter appeared in the New Scientist in 1972 (by the way, the previous letter is by Norris McWhirter, of Guinness Book of Records fame):

As a further postscript, taking the world typewriting championships back to Canada in 1937 led to the Cromwell Cup for US versus Canada typewriting contests:

3 comments:

Wow!! I think I will take up type training again, especially the page flip seems a rare achievement.

I can hardly imagine doing what these champion typists did. It's not a particularly pleasant idea, either, to become purely "part of the machine"!

Hello,

George Hossfeld is my grandfather and he taught me how to type from the "Brief Typing" book that he authored. Just thought you might like to know that my father, George Hossfield, Jr. just passed away last May and in his house we found MANY things from my grandfather's typing days, including his last typewriter. It is always fun for us to see what other people find about him. He was truly an exceptional man, full of integrity, but he enjoyed a good laugh, too. He also played the piano beautifully and could play anything you asked. One of my brothers has his piano now. Thank you for saying such kind things about him. I still miss him.

Post a Comment